Panel 1

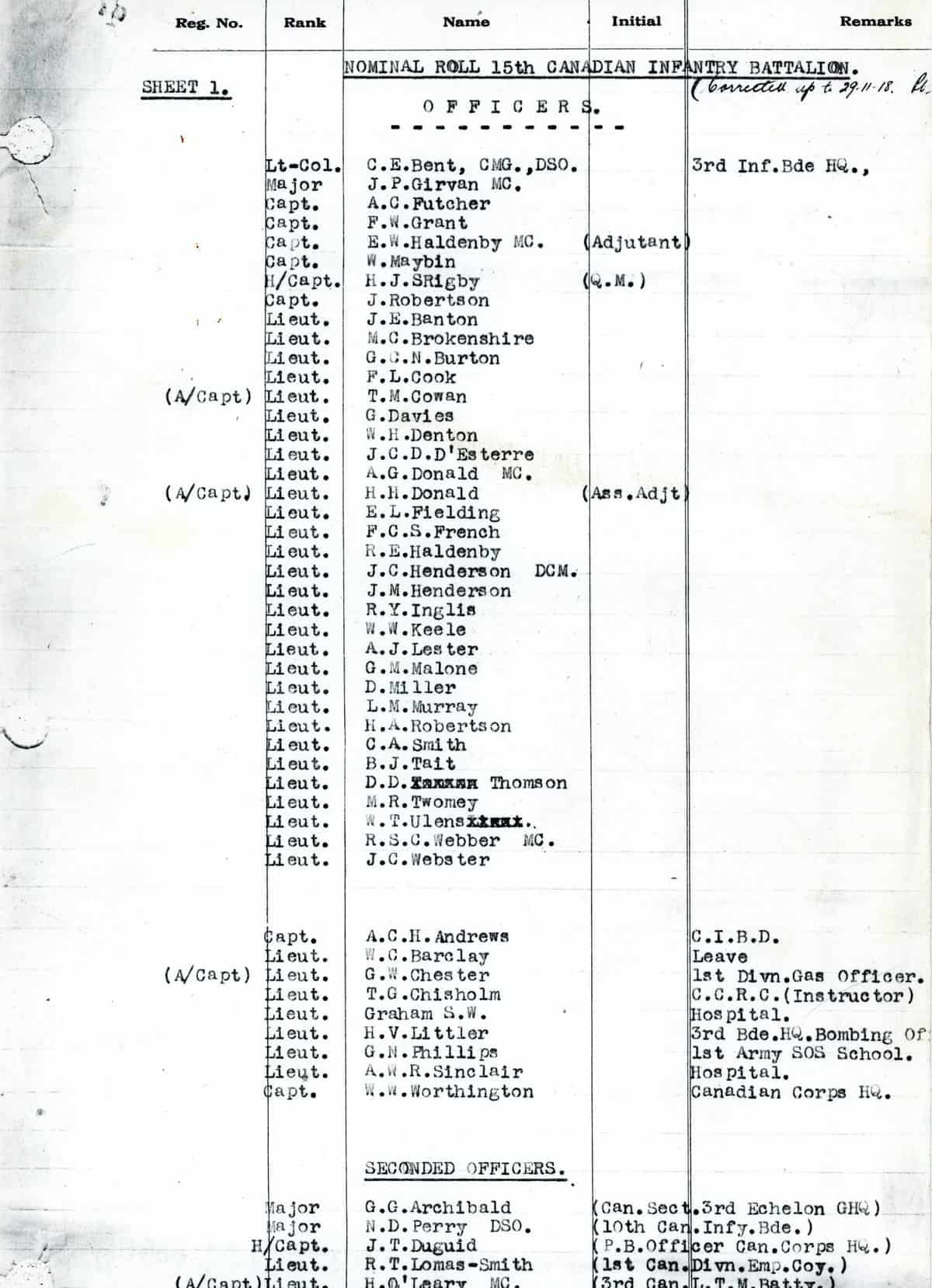

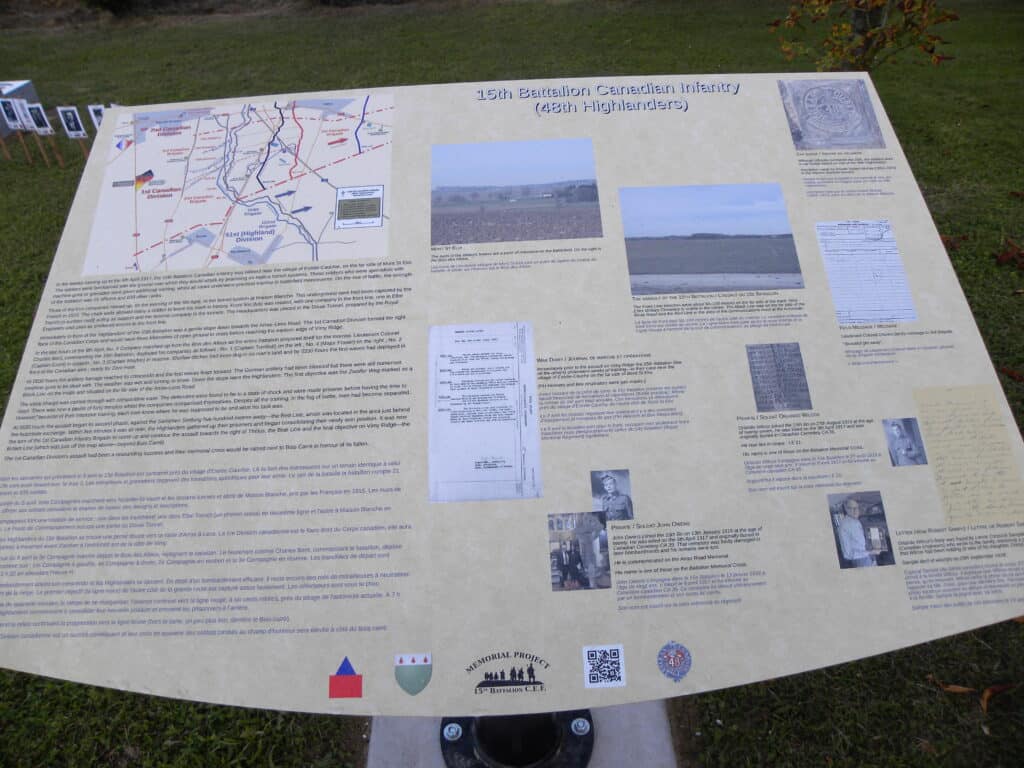

In the weeks running up to the 9th April 1917, the 15th Battalion Canadian Infantry was billeted near the village of Estrée-Cauchie, on the far side of Mont St Eloi. The soldiers were familiarised with the ground over which they would attack by practicing on replica trench systems. Those soldiers who were specialists with machine guns or grenades were given additional training, whilst all ranks underwent practical training in battlefield maneuvers. On the eve of battle, the strength of the battalion was 21 officers and 839 other ranks.

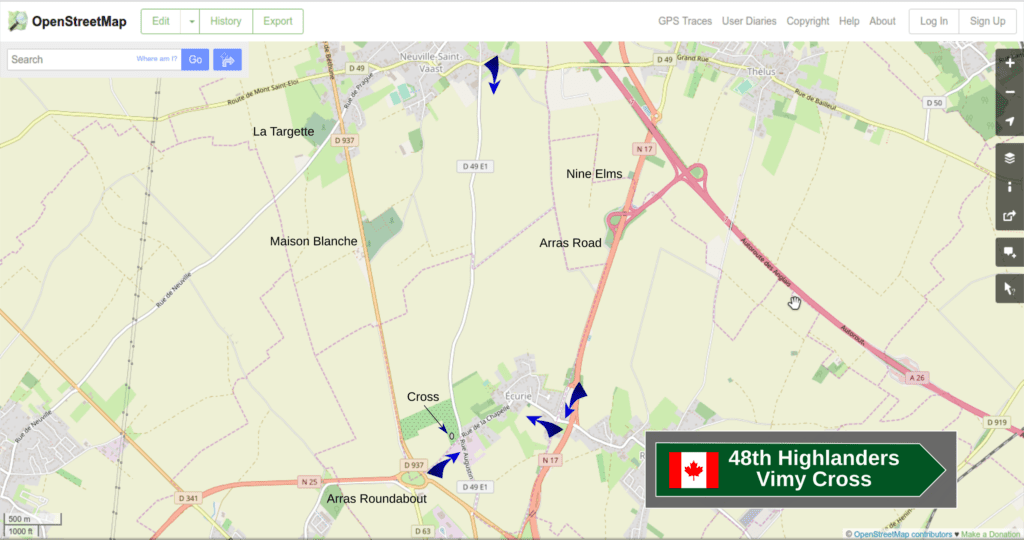

Three of the four companies moved up, on the evening of the 5th of April, to the tunnel system at Maison Blanche. This underground cave had been captured by the French in 1915. The chalk walls allowed many a soldier to leave his mark in history. Front line duty was rotated, with one company in the front line, one in Elbe Trench (a sunken road) acting as support and the reserve company in the tunnels. The Headquarters was placed in the Douai Tunnel, prepared by the Royal Engineers and used as sheltered access to the front line.

Immediately in front of the ‘Highlanders’ of the 15th Battalion was a gentle slope down towards the Arras–Lens Road. The 1st Canadian Division formed the right flank of the Canadian Corps and would have three kilometers of open ground to cross before reaching the eastern edge of Vimy Ridge.

In the late hours of the 8th of April, No. 3 Company marched up from the Bois des Alleux as the entire battalion prepared itself for the morrow. Lieutenant Colonel Charles Bent, commanding the 15th Battalion, deployed his companies as follows: No. 1 (Captain Turnbull) on the left; No. 4 (Major Fraser) on the right; No. 2 (Captain Grant) in support; No. 3 (Captain Maybin) in reserve. Shallow ditches had been dug in no man’s land and by 0330 hours the first waves had deployed in front of the Canadian wire; ready for Zero Hour.

At 0530 hours the artillery barrage reached its crescendo and the first waves leapt forward. The German artillery had been silenced but there were still numerous machine guns to be dealt with. The weather was wet and turning to snow. Down the slope went the Highlanders. The first objective was the Zwolfer Weg marked as a Black Line on the maps and situated on the far side of the Arras– Lens Road.

The initial charge was carried through with comparative ease. The defenders were found to be in a state of shock and were made prisoner before having the time to react. There was now a pause of forty minutes whilst the companies reorganized themselves. Despite all the training, in the fog of battle, men had become separated. However, because of their intensive training, each man knew where he was supposed to be and what his task was.

At 0655 hours the assault began its second phase, against the Swischen Stellung five hundred meters away—the Red Line, which was located in the area just behind the Autoroute exchange. Within five minutes it was all over, the Highlanders gathered up their prisoners and began consolidating their newly won position. It was now the turn of the 1st Canadian Infantry Brigade to come up and continue the assault towards the right of Thélus, the Blue Line and the final objective on Vimy Ridge—the Brown Line (which was just off the map above—beyond Bois Carré).

The 1st Canadian Division’s assault had been a resounding success and their memorial cross would be raised next to Bois Carré in honour of its fallen.

Panel 2

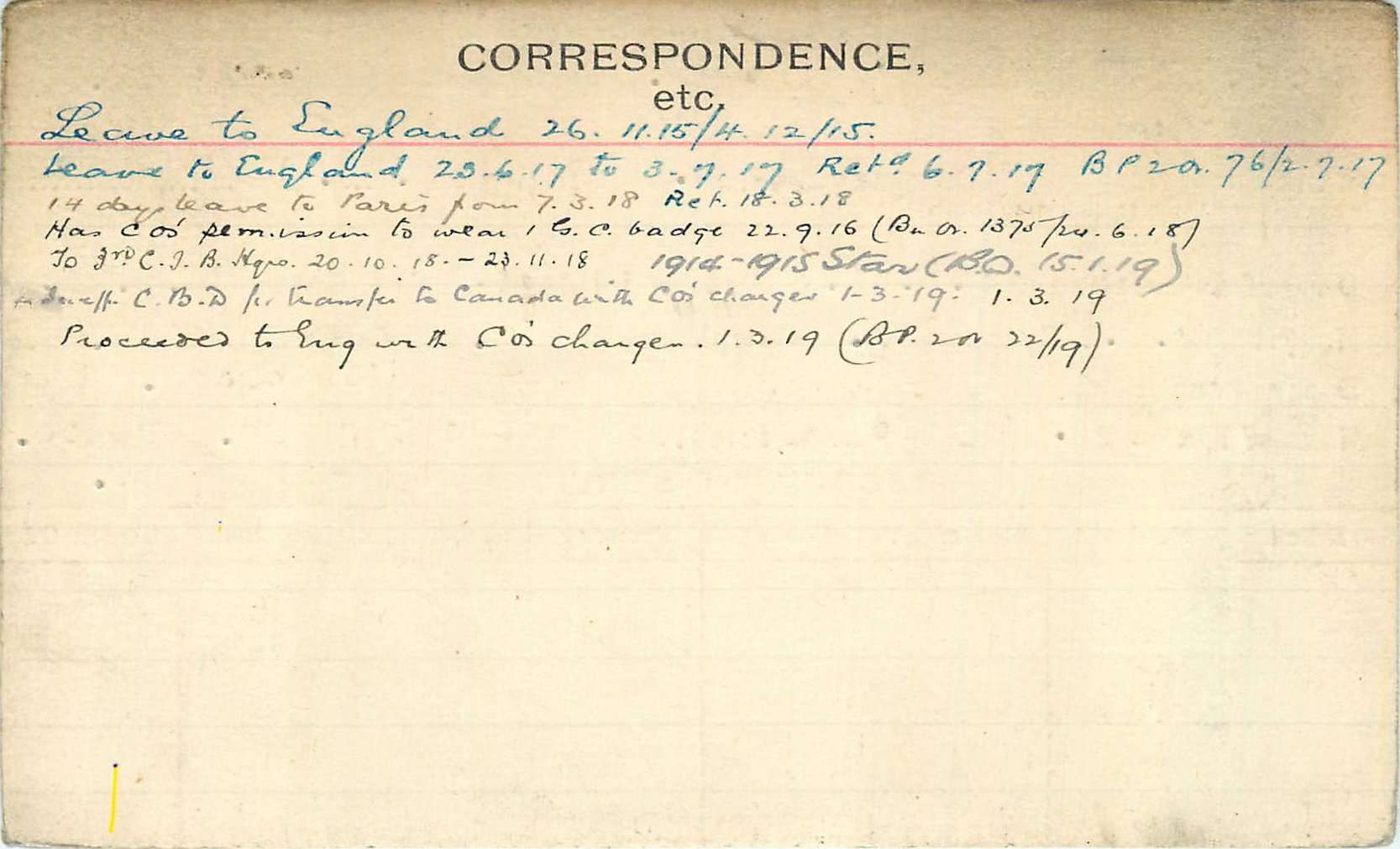

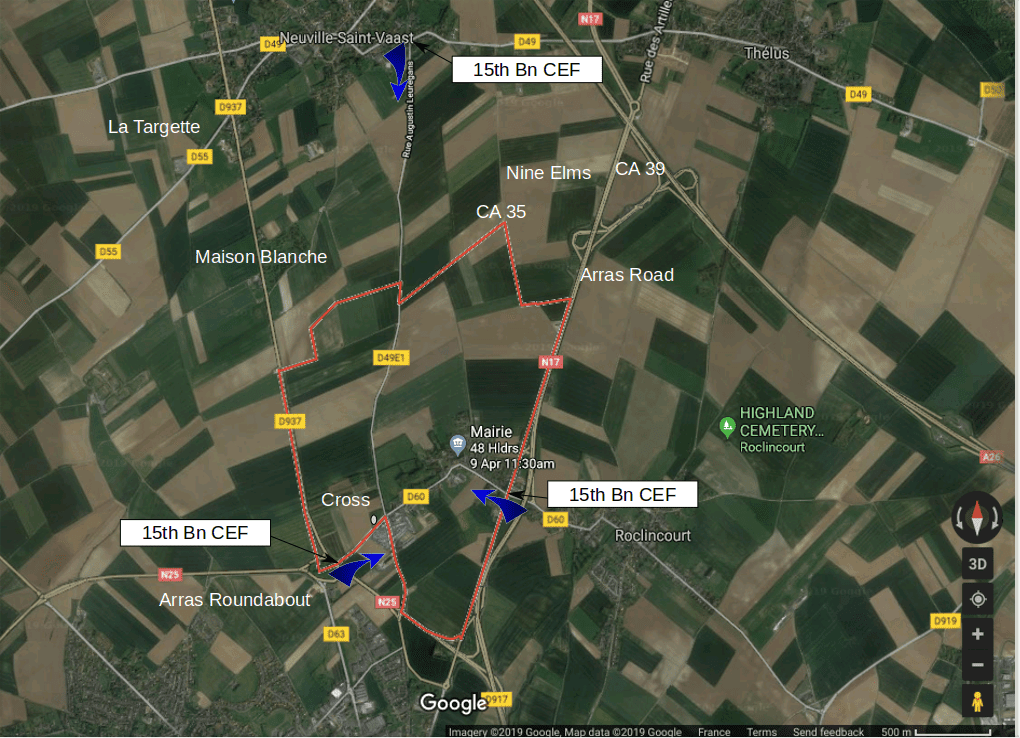

In preparation for the assault, units were assigned specific locations for the collection and burial of their dead. The majority of the 15th Battalion men who fell during the attack were buried at locations coded as CA 35 and CA 39, with 23 in the former and 39 in the latter. CA 35 was located close to the exit of the Douai Tunnel while CA 39 was located close to the main Arras Road.

The Regimental History suggests that the 15th Battalion’s wooden cross was erected at CA 39. However, this burial site (in the wooded area on the far side of the Arras Road) was almost completely destroyed by subsequent shelling causing the loss of almost all of its graves. Detailed research reveals that although CA 39 contained more 15th Battalion graves than CA 35, only the latter is referred to as a ‘regimental cemetery’ containing, as it did, nothing but 15th Battalion graves. As CA 35 was further to the rear, the battalion carpenter would have been able to work in relative safety. The fact that CA 35 and all its graves survived the war intact and the cross is unmarked by shellfire would further suggest that the only surviving photograph is of CA 35.

Following the 1918 Armistice, the twenty-three graves from CA 35 were exhumed and reburied in Plot II of Nine Elms Military Cemetery—originally created by the 14th Battalion, Royal Montreal Regiment. Only three graves from CA 39 remained identifiable and these can be found in Plot IV. The other burials in CA 39 were lost and are now commemorated in a special memorial along the front of the cemetery. It should be noted that CA 39 was originally known as the Arras Road Cemetery, it should not be confused with the Arras Road British Cemetery.

A 1919 French photographic postcard clearly shows that the 15th Battalion’s Vimy cross (large cross, second from left foreground) had been moved to Nine Elms Military Cemetery at the same time as the relocation of the graves.

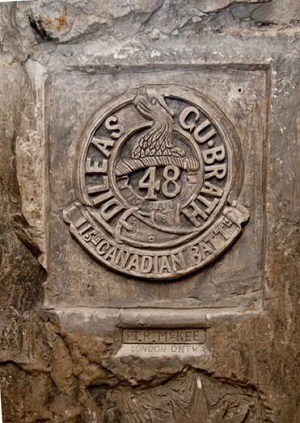

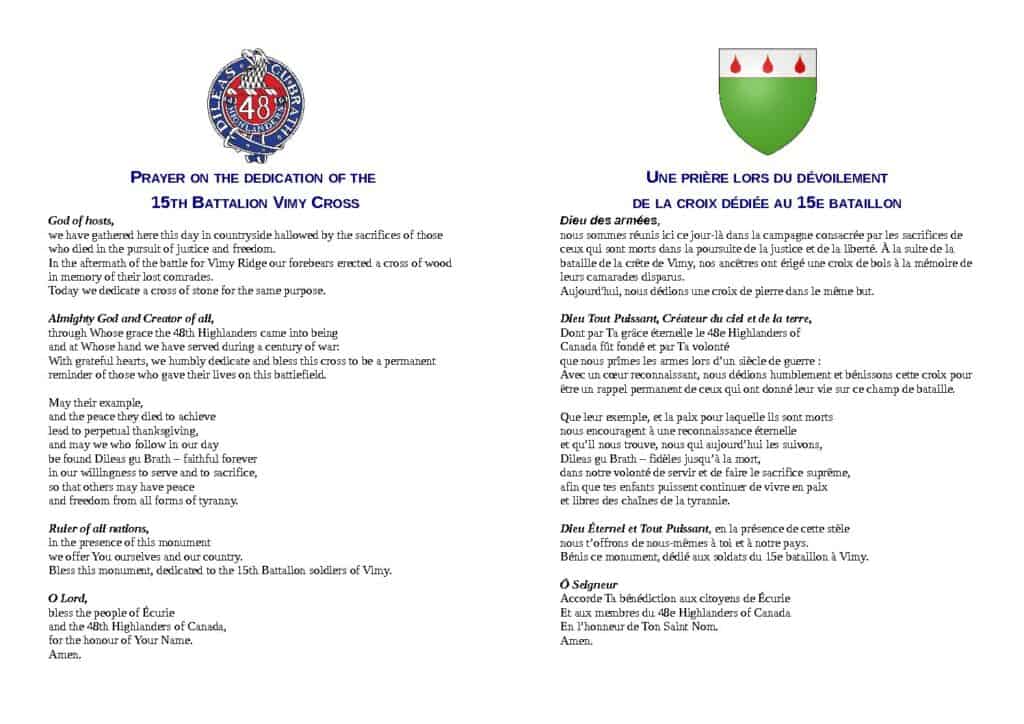

Subsequently, between 1919 and 1923, the CWGC reconstructed Nine Elms Military Cemetery into the permanent pattern seen there today, and all the wartime memorial crosses were removed. In 1923 the 48th Highlanders of Canada acquired the 15th Battalion’s Vimy cross from the CWGC and brought it home to the unit’s Armoury in Toronto. The cross was installed on the wall above the main parade square and unveiled in a ceremony on 30th October 1925.

When the Armoury was demolished in 1963, the Vimy cross was moved to the regimental museum which was located in the 48th Highlanders’ Memorial Hall. The regimental museum moved to its current location at St Andrew’s Church on Simcoe Street in Toronto in 1997 and the Vimy cross has been on permanent display there ever since.

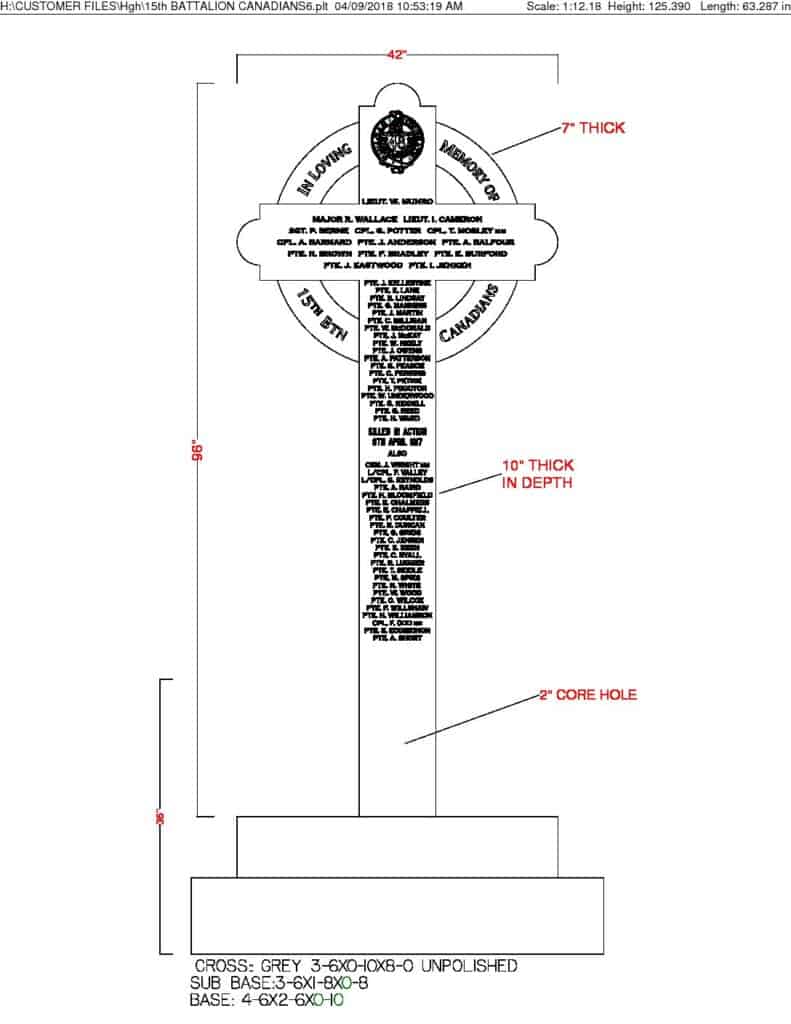

The Roll of Honour

One of the mysteries of the cross is why some names are on it, but others are missing. All of those soldiers buried at CA35 feature as an addition to the original listing, yet not all of those buried at CA 39 were included at the top. A few names were added later, perhaps as news reached the carpenter, and the final name, Lieutenant Munro, was killed on 1st May 1917. The battalion only returned to the area on a few more occasions so perhaps it wasn’t possible to add more names. We will probably never know.

This list includes all of the Vimy casualties from 9th April 1917 until the end of May 1917 plus those from June who are buried in the cemetery. Stanley Effinger was the final Vimy casualty to die of his wounds.