Trench warfare in the Great War was employed primarily in an area in northern France and Belgium known as The Western Front. It developed in late 1914 as the opposing armies dug in to prevent flanking attacks from the other.

The armies of World War I were constituted as they were a century before and soldiers previously equipped with bayonets and inaccurate rifles now faced heavy artillery, machine-guns capable of 400 rounds per minute and precision-firing small arms. The result was that the armies – and mainly the infantry -regardless of size or strategy, were largely defenceless against this new firepower, particularly when advancing. Generals, who had no effective tactical solutions, soon resorted to trench warfare as a fundamental strategy designed not only to protect troops but to also to at least hold their positions.

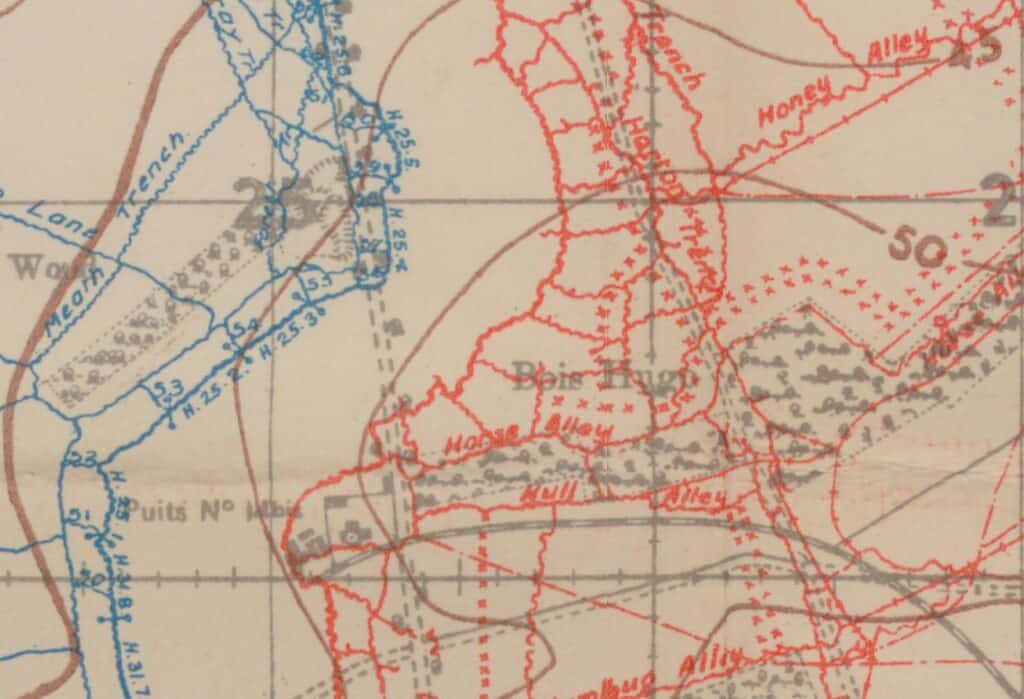

At its core, trench warfare was a form of defensive warfare intended to halt enemy advances. The parallel opposing trench systems – often less than 100 yards apart, were extensive, complex and designed to hinder enemy assault while allowing for fall back positions.

Long, narrow trenches were dug into the ground, usually by the infantry who would occupy them, and by late 1916 the Western Front contained more than 1,000 kilometres of frontline, support, reserve and communications trenches.

Having multiple lines of trench allowed soldiers to retreat if the frontline trench was overrun or destroyed by the enemy. Reserve trenches also provided relative safety for resting soldiers, supplies and munitions.

Trenches were usually dug in a zig-zag pattern rather than a straight line to prevent gunfire or shrapnel from being projected along the length of a trench, if a shell or enemy soldier ever landed inside. The pattern is visible in an aerial photograph of a trench network which shows German trenches on the right, Allied trenches on the left and ‘no man’s land’ between them.

The area between the opposing front line trenches – known as ‘no man’s land’ – was a veritable nightmare strewn with mines, shell craters, mud, unexploded ordinance, barbed wire and countless bodies.

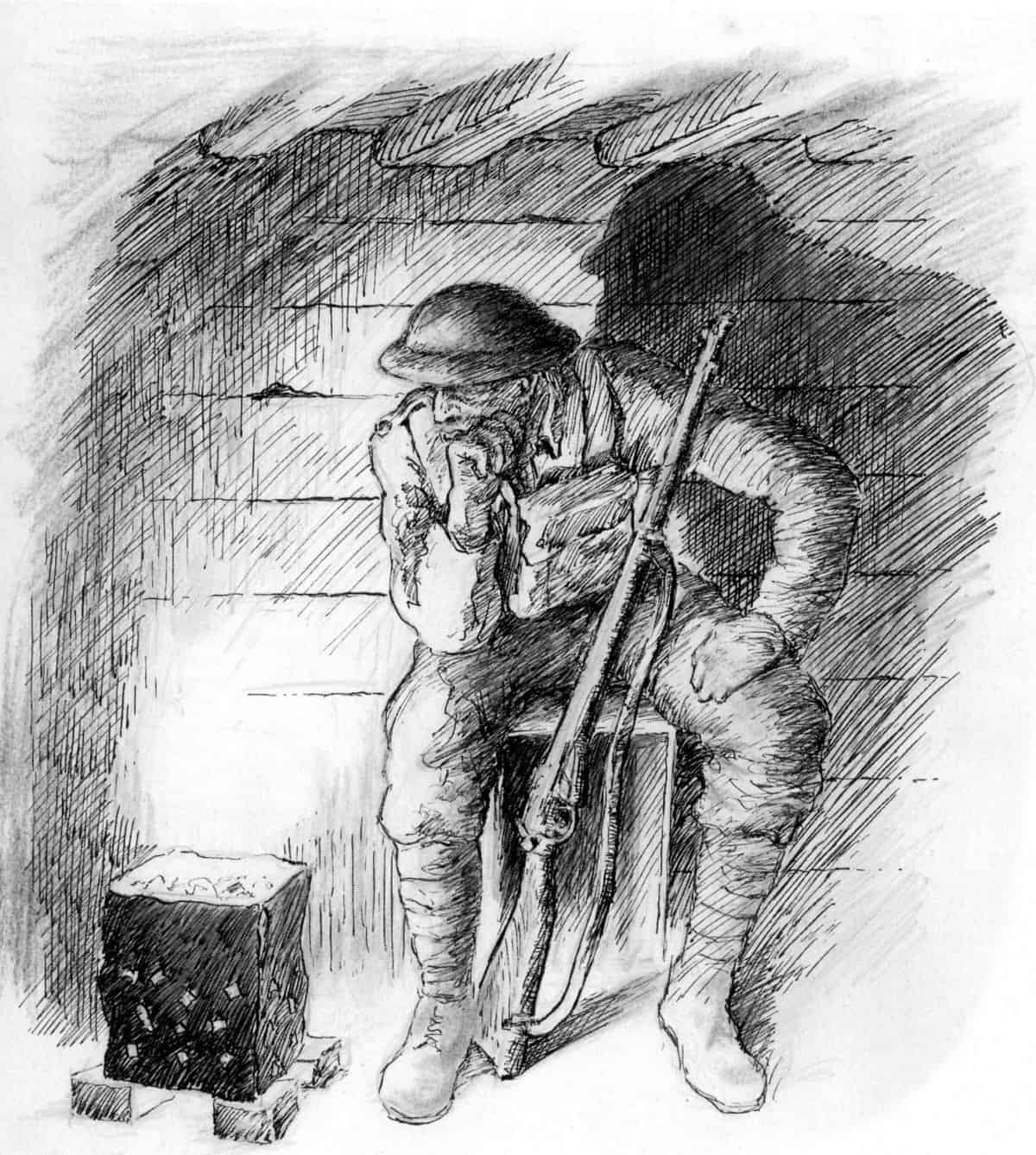

Other common features of Western Front trenches were dugouts (underground shelters) and ‘bolt holes’ or ‘funk holes’ (sleeping cavities hacked into trench walls). Most digging and maintenance work in the trenches took place at night, under cover of darkness, so soldiers often spent daylight hours huddled and sleeping in these small spaces.

Attacks from the trenches were made by climbing over the forward edge of the front line trench (known as going ‘over the top’ or ‘hitting the bags’ ) and attempting to cross ‘no-man’s land’ under a barrage of artillery and small arms fire to reach the opposing enemy’s line of trenches. This type of warfare was difficult and dangerous and because of the nature of the fighting and the adverse conditions, it frequently resulted in heavy casualties.

The dangers of trench warfare were plentiful. Enemy attacks on trenches or advancing soldiers could come from artillery shells, mortars, grenades, underground mines, poison gas, machine guns and sniper fire.

Soldiers in the trenches endured conditions ranging from barely tolerable to utterly horrific. Exposed to the elements, trenches filled with water and became muddy quagmires. One of the worst fears of the common Western Front soldier was ‘trench foot’: gangrene of the feet and toes, caused by constant immersion in water.

The duties of a trench soldier varied widely. Maintenance – digging new trenches, repairing old ones, draining water, filling sandbags, building parapets and unfurling barbed wire – was never-ending (some soldiers’ accounts tell of more back-breaking labour than actual fighting).

Nighttime in the trenches was both the busiest and the most dangerous. Under cover of darkness, soldiers often climbed out of their trenches and moved into ‘No Man’s Land’ where work parties repaired barbed wire or dug new trenches. More aggressive operations involved patrolling for enemy activity or conducting raids to kill or capture enemy troops or to gather intelligence

Trench life witnessed a steady trickle of death and maiming. Outside of formal battles, snipers and shells regularly killed soldiers in the trenches. This regular death toll – referred to as ‘trench wastage’ – ensured the need for constant reinforcements. In the 800-strong infantry units, “wastage” rates were as high as 10 percent per month, or 80 soldiers killed or incapacitated.

With soldiers fighting in close proximity in the trenches, usually in unsanitary conditions, infectious diseases such as dysentery, cholera and typhoid fever were common and spread rapidly. Trench soldiers also contended with ticks, lice, rats, flies and mosquitos.

As they were often effectively trapped in the trenches for long periods of time, under nearly constant bombardment, many soldiers suffered from “shell shock” – the debilitating mental illness known today as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Following morning stand-to, inspection, and breakfast, soldiers undertook any number of chores, ranging from cleaning latrines to filling sandbags or repairing duckboards. During daylight hours, they conducted all work below ground and away from the snipers’ searching rifles. In between work fatigues, there was often time for leisure activities.

A typical day in the trenches

Time | Activity |

5am | ‘Stand-to’ (short for ‘Stand-to-Arms’, meaning to be prepared for enemy attack) half an hour before daylight |

5.30am | Rum ration |

6am | Stand-down half an hour after daylight |

7am | Breakfast (usually bacon and tea) |

8am onwards | Clean selves and weapons, tidy trench |

Noon | Dinner |

After dinner | Sleep and downtime |

5pm | Tea |

6pm | Stand-to half an hour before dusk |

6.30pm | Stand-down half an hour after dusk |

6.30pm onwards | Work all night with some time for rest (patrols, digging trenches, putting up barbed wire, getting stores) |

Trench tours and rotation

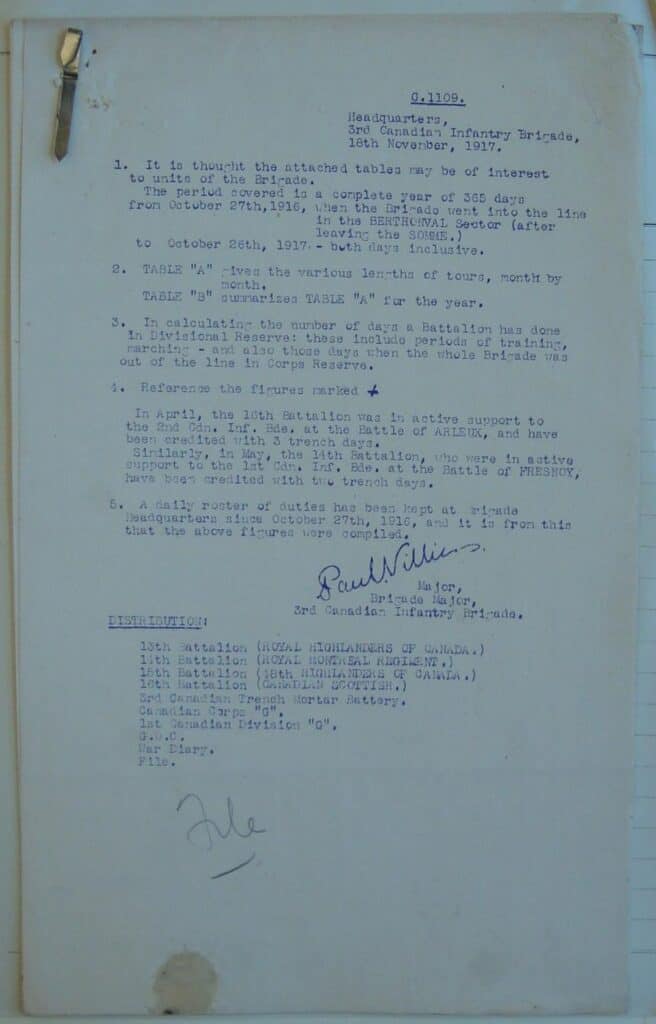

Soldiers did not spend all or even most of their time in frontline trenches as a rotation system was used by the Divisions, Brigades and Battalions to provide a break from the stress of combat and trench life as well as to allow time for training, preparation for future operations, re-quipping, etc and occasional leave for individual soldiers.

This rotation system, referred to as ‘trench tours’, saw units spend four to six days in the frontline trenches before moving back and spending an equal number of days in the support and, finally, the reserve trenches. Unless a major offensive was imminent, the normal trench tour saw most men spending six days in the trench system and six days well back from the front line. Only two or three days of this six-day rotation was spent in the frontline trench itself; the rest was spent in reserve or support trenches.

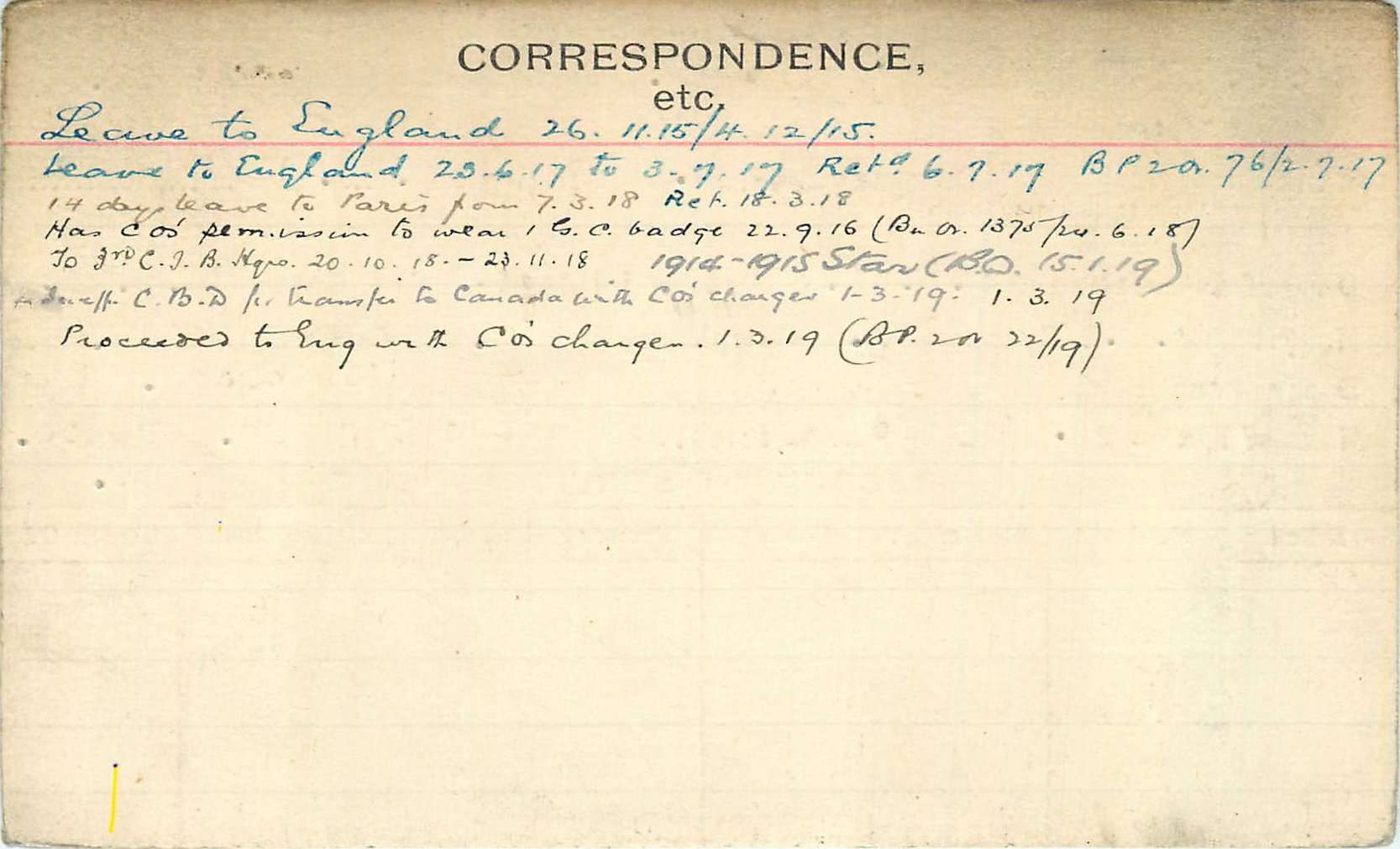

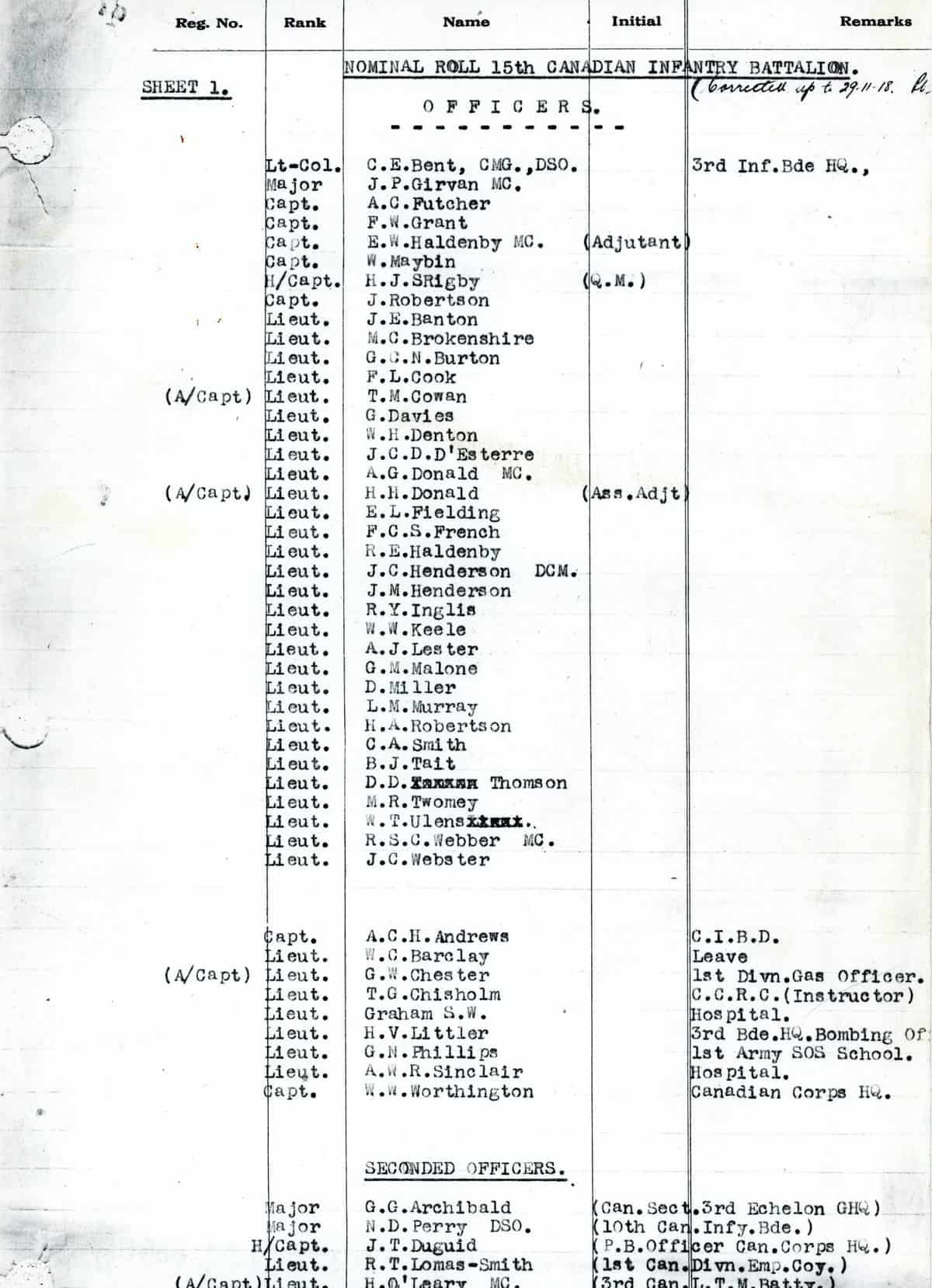

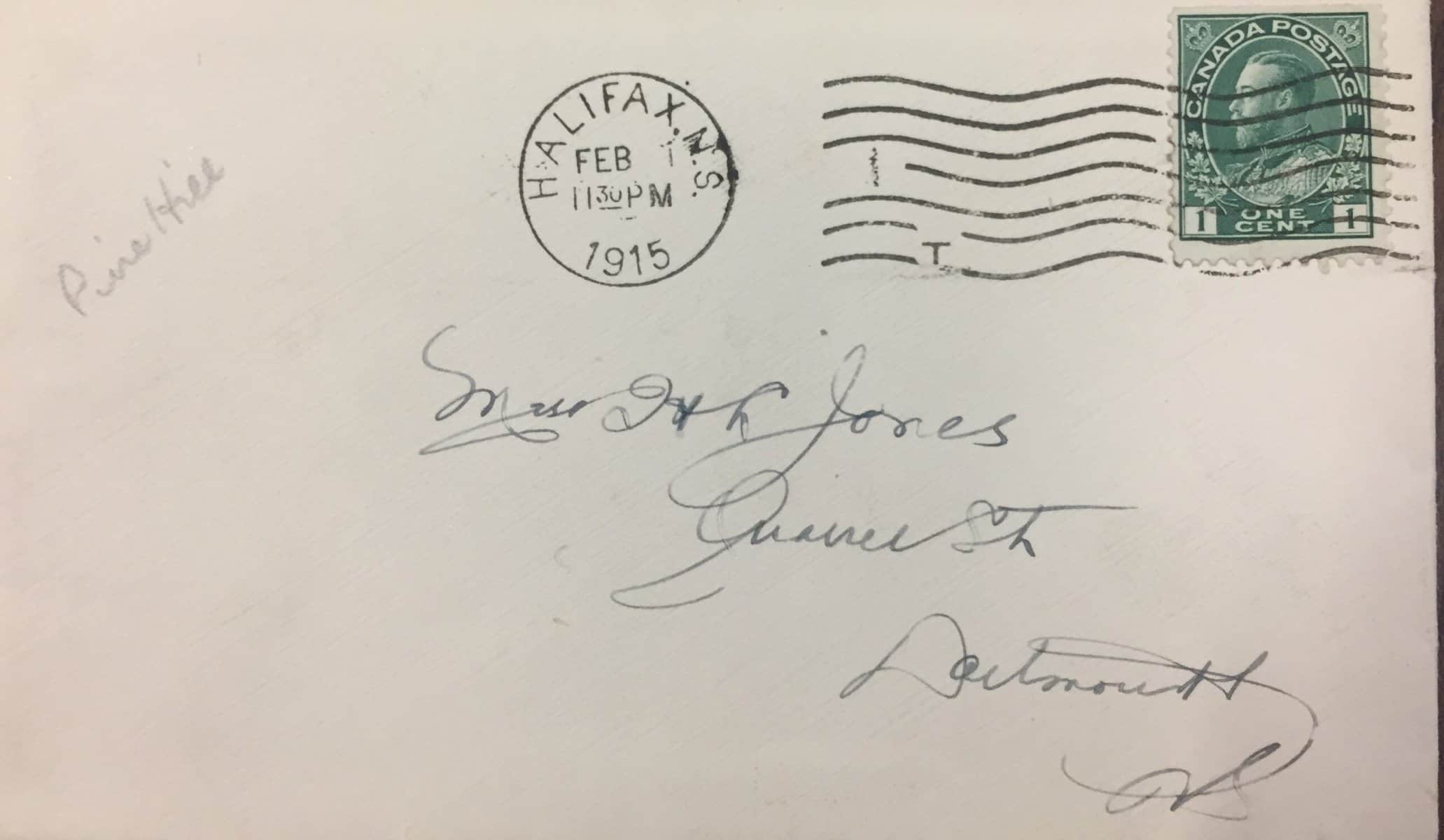

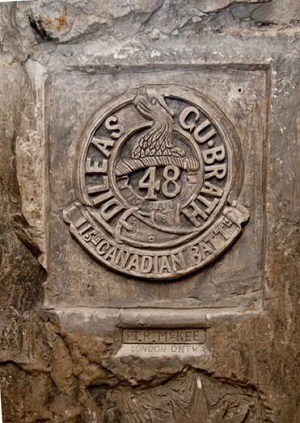

The documents on this page are digital images of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Brigade’s trench tour or rotation schedule for the period 27 October 1916 to 26 October 1917. They show the various lengths of tours month by month for the 13th, 14th, 15th and 16th Battalions.