Salutes may be fired with personal weapons, field pieces, or ship’s cannons. The origins of such salutes are a little obscure. Making a loud noise has long been regarded as a form of celebration. Another suggestion is that the salute was originally a sign of trust, originating around the 14th century. In the days of muzzle-loading cannons, it took a while to reload a ship’s armament once it had been fired. So when a ship was approaching a foreign port or another friendly ship, all the cannons on board would be fired to show that they were empty and posed no threat. It was also a sign of trust that people on land or in the other vessel not to open fire on them. In time, this practice was adopted as a way to honour dignitaries on land as well.

The salute today is not fired in one large burst of gunfire but rather as a rolling volley, in which one weapon fires after another. It’s said that this practice originated in less chivalrous, more pragmatic times. By firing one gun after another, a symbolic salute could be fired to honour a VIP, but some guns would remain loaded so as not to leave the vessel wholly defenseless. A specific number of guns is fired to honour VIPs in accordance with their status. Royalty and heads of state receive a 21-gun salute, field marshals, state officials and equivalents receive a 19-gun salute, generals and equivalent ranks receive 17, and so on down to 11 for a brigadier.

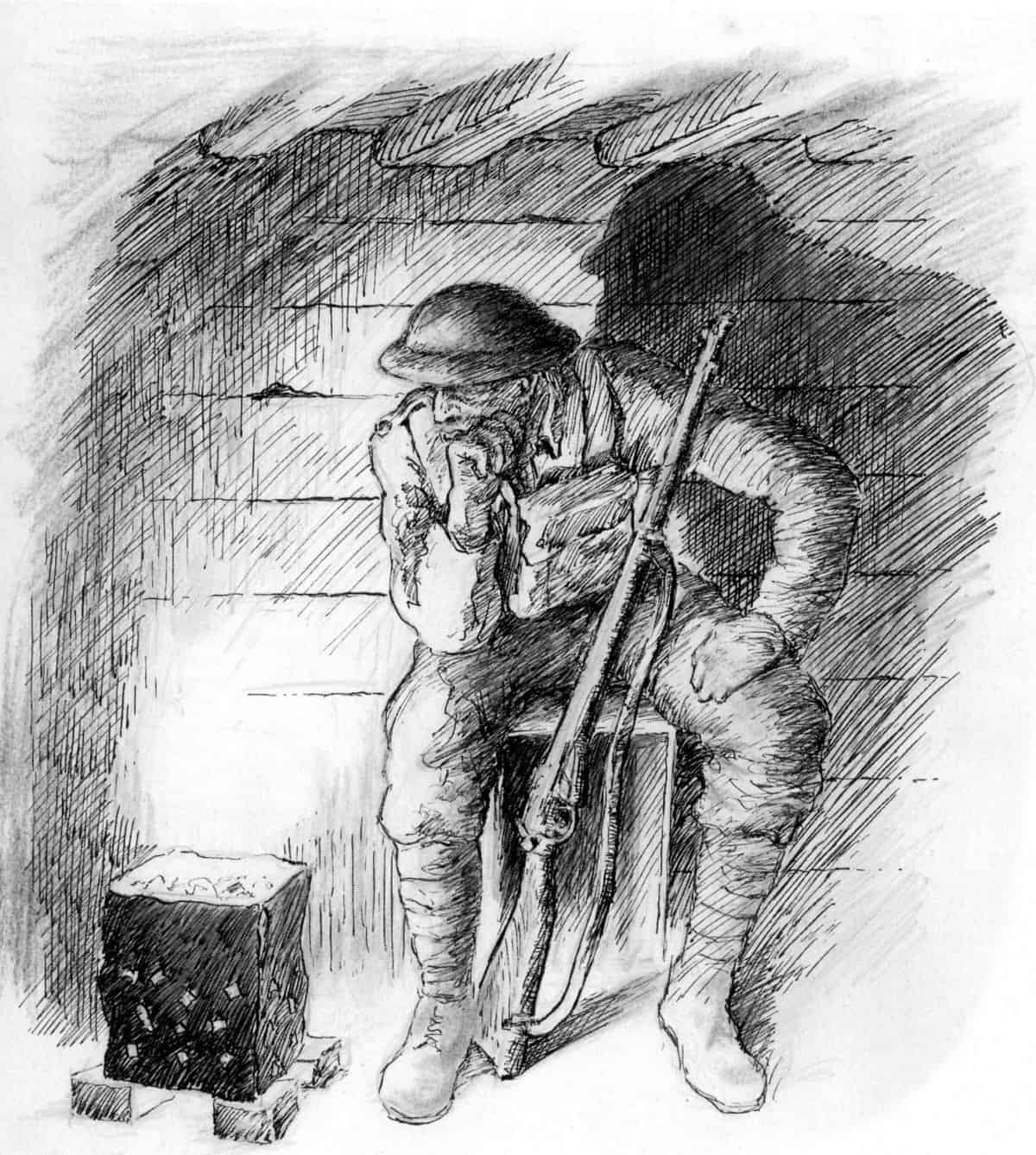

To honour the passing of a soldier below the rank of brigadier, or as a general gesture of mourning and remembrance, three rifle volleys are fired; all the rifles are fired in unison, and this is repeated three times. The three volleys are believed to have originally represented the holy trinity. Other sources, however, trace the practice to more ancient origins: at pagan funeral ceremonies to honour dead warriors, their comrades rode three times around the funeral pyre.